Metonymy Press’s latest release, El Ghourabaa: A Queer and Trans Collection of Oddities, had its Montreal launch on Saturday, June 15th at Brique par brique’s offices in Park-Ex. This anthology was edited by Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch, author of award-winning books The Good Arabs and Knot Body, and Samia Marshy, who has been editing for years but for whom this is her first publishing experience.

The two talked to me about how they navigated putting El Ghourabaa together in the midst of “Israel’s” latest genocidal campaign while they and several contributors were grieving, what it means for them to be able to include the late Etel Adnan in their anthology, and the highs and lows of the publishing process.

Answers have been edited for clarity.

Sophie Dufresne: In the introduction to El Ghourabaa: A Queer and Trans Collection of Oddities, you state how the anthology “started as a project to celebrate the fullness of queer Arab and Arabophone identity. As we endure months of dehumanization and violence by the media and the colonial nation-states, it feels more important than ever to assert ourselves, even if we are not in a celebratory mood. Our existence is resistance.” What is your hope for El Ghourabaa’s impact on the literary community and beyond?

Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch: I wanted to do this project for a long time; since, I would say, 2016. So it’s been something I’ve been thinking about for a while. I always thought, “Eventually I will do this.”

I did a Jeunes volontaires project and began working on this anthology, and Ashley [Fortier, Metonymy co-publisher] was my mentor. I worked on the project alone for about a year and a half before I decided that I wanted to bring in another editor, so I asked Samia.

There was this original idea of what I wanted that kind of changed as we collaborated, because that always happens when there’s more than one person involved. It didn’t change drastically, but you know, it was nice to have another person’s perspective.

Then October 7 happened while we were still working on [El Ghourabaa]. And obviously, that shifted things and slowed the process down. We wanted to be working on this project, but also we wanted to make a lot of space for people to be in anger and grief, including us, and not rush the project. So the project was definitely delayed, which was a good thing, ultimately.

Samia Marshy: With everything going on, I think it would have been a mistake, and just really hard emotionally to try and put the book out in the fall, which was the original plan. [We wanted] to make space and respect the terrible thing that was happening.

El Bechelany-Lynch: Yeah, and we felt weird, sending emails being like, “Please send us your bio!” when people were grieving, and in shock, and organizing, and upset, and all these things. But then, it felt nice to have this project to work on once things continued, and we were in a different place than that initial shock and grief. We’re not necessarily in a celebratory mood, but also, [we’re] in a space where queer people, and especially queer Arabs are being utilized by “Israel” to—

Marshy: promote a genocidal agenda.

El Bechelany-Lynch: Yeah, it feels important to be like “No, fuck that.”

Marshy: We make our own space.

El Bechelany-Lynch: Yeah, and that’s not being asked. Queer Arabs and queer Palestinians aren’t [saying], “Yes, please do this on my behalf.” We can be like, “Fuck you, this is for us.” You know? We also donated our advances to an organization in Montreal, Mubaadarat, who’s been doing a lot of stuff with queer Arabs, and to a queer organization, alQaws, in Palestine because we wanted what little money we made from this project to be able to be helpful. We didn’t want to profit from this genocide, from this weird moment where people really want to read Arab work.

I mean, anthologies don’t make money, so it’s not like we were like, “We’re gonna rack in the money from this.” But I think we want it to be explicitly anti-colonial and anti-genocidal, which, you know, shockingly, is somehow not the baseline. A book that was in opposition to a lot of harmful things, and also celebrating the beauty of queer and trans Arabness and queer and trans Arabophones too.

Marshy: I think one of the things that we talked about a lot when we were envisioning what kind of pieces we wanted and what we wanted the book to look like was that we didn’t want necessarily an anthology that was [asking,] “What does it mean to be queer and Arab?” Because I think there’s a lot of think pieces around [those identities] for people from all kinds of diaspora. And that’s kind of the stereotype: that it’s hard to hold both of those identities. But no, it’s a given that there [are] queer Arabs, and we want to know what you’re thinking about, what you want to write about, and [we want to] see your art. [We wanted to hear from] people who are coming from that positionality but [who] aren’t necessarily conflicted about that positionality.

El Bechelany-Lynch: Yeah, and how do you incorporate your queer or trans Arabness into your work without having it have to be a think piece, which is such a white hetero demand of racialized people and queer people to be like, “Tell us about yourself!”

Marshy: It’s a request for legibility while simultaneously othering. What if we [say], “Actually, we are the standard.” It’s a given that these identities coexist, so then what?

El Bechelany-Lynch: We’re both interested in work that pushes the bounds and is explicitly weird, and tries to fuck with genre and fuck with language and is really playful. And we got so much good stuff.

“It’s a given that these identities coexist, so then what?”

-Samia Marshy

Dufresne: Yeah, I’m excited to read it again! El Ghourabaa contains writings from individuals of very different walks of life, as you’ve been mentioning. The introduction talks a bit about what you were looking for and what you got, but what did the selection process look like, and were there any pieces that almost made the cut but that you unfortunately couldn’t include in the collection?

Marshy: I mean, we got over 100 submissions. So I can’t say off the top of my head that there [are] any pieces that I wish that we had included. It was a few weeks of so much reading, and I feel really good about every piece that we took. I think the unfortunate side of not having a lot of books like this is that there’s like for sure so many submissions that I wish that we could have included, but that we couldn’t because there was just not enough space.

El Bechelany-Lynch: I think that one thing is that it’s definitely pretty North American centred. And that was going to happen because the book is mainly in English. And the other language that I could translate from is French. So we already knew that that was going to be limiting. And we got writers who don’t live in North America, and that was already really exciting. Part of me wishes that there could have been enough time and space and money to reach further.

If we had, in an ideal scenario, a third editor who was able to edit both in English and Arabic, which we didn’t, [then we would have been able to accept submissions that were in Arabic]. We were still able to include work with Arabic in it, which was important to us. Nofel’s [piece] has a lot of Arabic, and one of the poems is in both Arabic and English. So we got an outside editor to look at that. There is a lot of Arabic within the book that we were able to work with, because I can read and write it, but I’m not at the level of being able to edit in Arabic. And so that’s something that I wish there was more of, but also, we kept telling ourselves that the book—

Marshy: It can’t be everything.

El Bechelany-Lynch: It can’t be everything, yeah. And there’s only so much we can do with our limited budget and limited capacity as a team of two, and then two people on the publishing side.

Marshy: And then getting over 100 submissions. It was so much more admin than expected.

El Bechelany-Lynch: One thing I do wish is that we had more Arabophones who are not Arab. We don’t have any Sudanese contributors or Somali contributors, for example. And we tried to reach out to people, but there was only so much we could do. Mostly, I’m really happy with [the anthology].

Dufresne: Would you like to talk a bit about what it means for you to feature the late Etel Adnan in your anthology?

El Bechelany-Lynch: I have admired her work for a long time. And when she passed away, she was 96. And so she had been a pillar in the queer Arab writing community for so long. [She was] one of the first out publicly recognized Arab writers. And she’s always been explicitly anti-imperialist, explicitly pro-Palestine, and very political. Just someone who’s engaged in ways that I’m interested in and writing experimental, cool writing. And so I was like, “We have to have her in this, it’s so important.” And so many of the people who we chose to be in the anthology actually feel really indebted to her.

Marshy: And I know it’s very meaningful for so many of the authors to be in the same book as her. And so it’s really cool to be able to do that.

Dufresne: Some of El Ghourabaa’s contributors were solicited. What made you solicit the work from Rabih Alameddine?

Marshy: I think similarly to Etel Adnan, he’s a pillar of queer Arab literature. And he also writes fun, weird shit. We were able to gain the rights to this one short story of his that was published in a journal.

El Bechelany-Lynch: I initially wanted to feature something from Koolaids, because it’s his first novel, it’s really experimental and weird and takes place between Lebanon, [during] one narrator’s childhood, and San Francisco, during the AIDS crisis. There are a few gay men narrators, and it was this perfect combination of what we were looking for. We weren’t able to get the rights for that. If you’re a smaller press, you only have so much money to work with. If you’re working with a bigger press, they have so many more resources, and ins, and contacts, whereas, if you’re a small press, you kind of have to be like, “Hello, please give us the rights. Could you please not charge us 1 million dollars? This is a really important project!” and work from there.

So it was easier to get the rights for a short story that is not in a book that was previously published in The Paris Review where the author kept the rights. It was really just like a bureaucratic struggle to figure out what the right approach was.

Dufresne: In the same vein, what can you say about the publication process with large companies versus with smaller presses like Metonymy?

Marshy: Well, it’s my first experience publishing anything at all. And it’s been a really nice experience, working with Eli Tareq and working with Ashley and Oliver [Fugler, Metonymy co-publisher]. It’s nice to know exactly who you’re dealing with. When I’m talking to the people representing the publisher, it is the publisher. And there’s a lot of generosity and care.

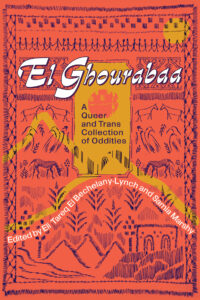

El Bechelany-Lynch: I specifically chose to go with Metonymy because I don’t want to work with bigger publishers. I like several things about working with a small publisher, like having a say in a lot of things. We got so much say in the cover, working with the artists that we wanted. Metonymy is always great about that. All the covers that Metonymy puts out are really beautiful and unique. And we both felt really strongly about the cover, so it was really nice to have that be given, that our input was going to be really present. Versus Penguin Random House, for example, where they would send it to the cover making machine, and people would make a generic cover [with] several blobby colours because racialized writers always get blobs as their cover. I refuse to have a blob cover. But that’s a small thing among many things. As Samia was saying, it’s nice to have such a caring experience.

Marshy: You don’t feel like you’re working with a machine. This is actually a couple of people. Metonymy, as a two-person publisher, has really punched way harder than their weight. Their books all do really well. They do really good work. You get the care experience of working with a small publisher, but also, they have a lot of experience and network, even if not financial resources, to help support the book process.

El Bechelany-Lynch: And it was a given that Metonymy would be pro-Palestinian. We knew that was going to be the case and did not have to worry about it. I can imagine being with a different publisher, who would use our book as a means to make them look good in this current moment, which would have felt awful and disgusting.

We had so many really important in-depth conversations with Ashley and Oliver about the weird feelings that we had about putting the book out right now. And they had so much flexibility.

Marshy: We wanted a portion of the money from the pre-orders to go towards Palestine, and they [agreed]. That’s not a given [when] working with other places. As people who are more directly affected by what’s happening, it’s nice to not have to also be dealing with the bullshit from shitty publishers.

El Bechelany-Lynch: Yeah. And having to advocate for ourselves. I just wish small publishers were given more money by funding bodies like Canada Council [for the Arts]. It just sucks that big publishers have all the money, and small publishers are struggling.

Dufresne: What has been the biggest challenge with El Ghourabaa?

El Bechelany-Lynch: I feel like some parts were really stressful, [which] can bring up tension in a friendship and [in a] collaborative experience, [but] we were able to move through that because we put a lot of care into our relationship in general, as editors together. I think the most difficult thing was admin. There’s so much admin for an anthology. And I knew that going in because I have friends who’ve done anthologies who were like, “It’s a lot of work!”

But no one said, “It’s a lot of work because you have to email 25 people.” And [you have to keep track of] everyone’s specific needs [surrounding communication styles]. And even with editing, you can’t put a one-size-fits-all approach with editing.

Everyone’s so different. When you have a very diverse group of people in an anthology who all work differently, you just have to [adapt].

Marshy: I think one of the things that I would do differently next time is have a big meet and greet early on in the process, once it’s official who all the contributors are. Because it’s vulnerable work. If I were to do that again, I would [want to] find a way to connect face to face earlier on in the process.

El Bechelany-Lynch: Yeah, and people have been waiting for this kind of anthology for a long time, so there [are] a lot of expectations. People were stoked about the existence of something like this. At the time, it was maybe going to be the first anthology of its kind. Now, it’s not, but it’s one of the first, which is still a lot of pressure. And I think a lot of people had specific ideas of what they wanted it to look like.

Dufresne: On the flip side, what are you the most proud of about this project?

Marshy: Just the whole project. I’m so proud of it. It looks so good. I’m really proud of Poline [Harbali] and Sultana [Garritano] because the cover went through so many iterations and I’m really grateful to both of them because we had so many opinions. And they did such a good job. I’m really proud that people responded to our call, contributed such amazing pieces, and allowed us to put this book together.

El Bechelany-Lynch: I’m so proud of just the sheer diversity of all of it. Not in a diversityTM type of way. But there’s just so many different types of work in it too, beyond different age ranges, different genders, different experiences, different countries, all these things. Everyone’s coming in from a weird little angle.

“As LGBTQ+ identity is becoming commodified and sold, there’s a PrideTM type pressure to sanitize queerness so that it can be sold as ‘family-friendly.'”

-Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch

Marshy: There’s a lot of sex, which we really wanted.

El Bechelany-Lynch: We need there to be not a sanitized version of queerness, but a version of queerness that can include sex and sexuality, without us having to worry “about the children.” I think in the current moment, as LGBTQ+ identity is becoming commodified and sold, there’s a PrideTM type pressure to sanitize queerness so that it can be sold as “family-friendly.” Sexuality is part of queerness, and [it is] being erased.

Dufresne: Is there anything else you would like to add?

Marshy: Be gay, do crime.

El Bechelany-Lynch: Be gay, do crime, free Palestine.

Sophie Dufresne studies creative writing at Concordia University in Tiohtià:ke/Montreal. They fell in love with poetry after reading “Hope” by Emily Dickinson in sixth grade and are now interested in the way form informs content (or is it the other way around?). They are the current publishing intern at Metonymy Press; an editorial intern at NiftyLit, a digital magazine; and the copy editor of The Encore Poetry Project, a local literary and arts initiative.